Bach, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Britten

In celebration of the twentieth anniversary of ArtistLed, David Finckel and Wu Han recorded a selection of timeless sonatas by J. S. Bach, Felix Mendelssohn, Claude Debussy, and Benjamin Britten.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata no. 1 in G Major for Viola da Gamba and Keyboard, BWV 1027

Felix Mendelssohn

Sonata no. 2 in D Major for Cello and Piano, op. 58

Claude Debussy

Sonata for Cello and Piano

Benjamin Britten

Sonata in C for Cello and Piano, op. 65

Artists:

David Finckel and Wu Han

“With endless gratitude, we dedicate this ArtistLed 20th anniversary release to producer and engineer Da-Hong Seetoo, whose musicianship, ingenuity, energy, loyalty, and pursuit of ever-increasing excellence have inspired us, and enabled ArtistLed to produce the recordings of our dreams.”

Notes on the Recording:

by David Finckel and Wu Han

Introduction

The genre of cello plus keyboard is represented here by works covering a period of at least 220 years. Taking the liberty of playing Bach’s Sonata for Viola da Gamba on the cello

(knowing what a big fan he was of the cello) is the only stretch of imagination in this project. The subsequent works on this recording faithfully document the development of the duo repertoire as well as accurately describe the musical climates of their times.

To say that each work on this recording is ingeniously conceived and composed would be an understatement. Indeed, all four works can be said to have pushed the possibilities for this wonderful combination of instruments far forward. Bach’s use of the two instruments to equally trade three voices back and forth firmly placed the gamba on an equal footing with the keyboard, and prompted listeners to hear the counterpoint between the gamba and each hand of the keyboardist with open ears. When Mendelssohn composed his second, highly mature cello and piano sonata, nothing like it had been heard before. It paved the way for composers such as Chopin, Brahms, Strauss, Grieg, and Rachmaninov to compose the grand romantic sonatas that so firmly cemented the cello’s reputation as an instrument equal in expressive potential to the violin. Nearing death in 1915, Claude Debussy encapsulated nearly every compositional innovation he had made (and there were many!) into this brief but highly potent sonata that once again opened the door for composers of the modern age to take the cello to new sound worlds. And that’s exactly what Benjamin Britten did in 1960 after hearing the cello played at the never-before (and never since) level solely in the possession of Mstislav Rostropovich.

The Works

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Germany; died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany)

Sonata no. 1 in G Major for Viola da Gamba and Keyboard, BWV 1027

Composed: before 1741

Other works from this period: Trio Sonata in G Major for Flute, Violin, and Continuo, BWV 1038 (1732–1735); Orchestral Suite no. 2 in b minor, BWV 1067 (ca. 1738–1739); Goldberg Variations for Solo Keyboard, BWV 988 (1741)

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

(Born February 3, 1809, Hamburg, Germany; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig, Germany)

Sonata no. 2 in D Major for Cello and Piano, op. 58

Composed: completed June 1843

Published: 1843, Leipzig

First performance: November 18, 1843, Leipzig

Other works from this period: Violin Concerto in e minor, op. 64 (1844); Andante and

Variations for Piano, Four Hands, op. 83a (1844); Piano Trio no. 2 in c minor, op. 66 (1845)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

(Born August 22, 1862, St. Germain-en-Laye, France; died March 25, 1918, Paris, France)

Sonata for Cello and Piano

Composed: 1915

Published: 1915, Paris

First performance: March 4, 1916, in Aeolian Hall in London by cellist C. Warwick Evans and pianist Ethel Hobday

Other works from this period: Book II of Préludes for Solo Piano (1911–1913); Jeux (Games) (ballet) (1912–1913); Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp (1915)

BENJAMIN BRITTEN

(Born November 22, 1913, Lowestoft, England; died December 4, 1976, Aldeburgh, England)

Sonata in C for Cello and Piano, op. 65

Composed: 1960–1961

Published: 1961

First performance: July 7, 1961 in Aldeburgh, England by cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and the composer at the piano

Other works from this period: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, op. 64 (opera) (1959–1960);

War Requiem for Vocal Soloists, Choirs, and Orchestra, op. 66 (1960–1961); Symphony for Cello and Orchestra, op. 68 (1963, rev. 1964)

About the Works

The selection of sonatas for this recording allows us a unique opportunity: to present in a single release works of greater variety than in any of our previous ArtistLed releases. Each piece represents a special, long-held passion of ours for the music of its composer and for the musical era in which it was created, and we were both thrilled and challenged to fold into one project the four distinct interpretational approaches that the works demand.

Like so many young musicians, we grew up on J. S. Bach: on the keyboard suites and inventions, the violin sonatas, partitas, and cello suites, and the mighty oratorios and thrilling concertos. Our little Sonata for Keyboard and Viola da Gamba, one of a set of three, is but a pea under the mattress of Bach’s enormous output. But as with all of Bach’s works, it contains a wealth of inspired content that innumerable lesser composers would have given anything to replicate. To play this music well requires, in equal amounts, the uncompromising discipline with which Bach himself worked, and the deep humanity that makes his music not only lovable, but indispensable. For this recording’s canvas, we selected the takes that included the most of both qualities from the dozens of run-throughs we had recorded, and the result says a lot about how we believe Bach should be approached.

In the summer of 2009, we mounted an edition of our annual summer festival, Music@Menlo, with the title “Being Mendelssohn.” Our admiration for and understanding of Felix Mendelssohn’s music deepened considerably through our research for the programming and through the process of conceiving a coherent three weeks devoted to Mendelssohn’s life and work. We were inspired to learn of Mendelssohn’s unceasing quest for knowledge, for ever-broadening his horizons and skills, for his commitment to education, and for his championing of J. S. Bach. It was therefore natural for us, in this recording, to follow Bach’s sonata with Mendelssohn’s masterful Second Cello Sonata, which includes not only signature Mendelssohnian brilliance in its outer movements, but a magical, Midsummer Night’s Dream-style movement in place of a scherzo, and a remarkable slow movement built on a Christian hymn in the piano answered by recitative-style (or cantorial, if you choose to hear it that way) utterances from the cello.

The pairing of Claude Debussy’s iconic sonata and the following sonata by Britten stems from multiple experiences in our musical lives. We virtually learned these pieces, as young musicians, from the historic recording by Rostropovich and Britten of both works. It is significant that these great artists chose to present Britten’s innovative sonata to the world in the company of a sonata by a composer roundly regarded as having paved the way for modernism in music. Debussy’s sonata, while beginning squarely in the key of d minor (a powerful segue from the Mendelssohn’s joyous D major ending) quickly moves into Impressionist harmonies and, in the Spanish-inspired second movement, flirts with atonality in ways that make this sonata sound contemporary even today.

Having finally acquired the printed music after practically memorizing the Sonata in C by Benjamin Britten from wearing out the LP recording, it became the first 20th century work that we put into our repertoire. (We subsequently recorded all of Edwin Finckel’s cello and piano music for ArtistLed, and also four sonatas composed for us by Bruce Adolphe, Lera Auerbach, George Tsontakis, and Pierre Jalbert “For David and Wu Han.”) The genesis of Britten’s sonata is one of the most exciting in modern music history: after hearing a performance in London of Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto by Rostropovich, in the company of Shostakovich, Britten met Rostropovich backstage and the two conspired immediately to collaborate on a new work for cello and piano. The story of the first reading, in which the two, experiencing too much anxiety, became totally inebriated beforehand (well-documented!), is the stuff of legend. The resulting relationship, one of the most fruitful ever between an instrumentalist and a composer, produced four more major works: three suites for solo cello, and the magnificent Cello Symphony, which set the bar at a new height for the genre of cello concerto.

A Note from David

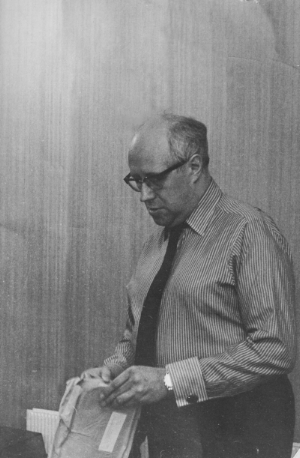

My pursuit of Rostropovich as a teacher led me to hunt him down soon after his release from the Soviet Union in May of 1974. He de-planed in London, and I embarked the next day on my first trans-Atlantic flight to seek him out. I guessed that he would visit his great friend Benjamin Britten in Aldeburgh, so I went there, found the Britten house (the “Red House”), and sat by the driveway under a tree, in the rain, for several days. Both Britten and his partner Peter Pears passed me many times with curious looks. That was as close as I came to Britten, and when Peter Pears finally found out what I sought, he wrote me a very gracious letter stating Rostropovich’s current whereabouts and permanent address. The below photo of Rostropovich I subsequently took myself in the London offices of Victor Hochhauser, and it shows him opening one of hundreds of invitations in the room from orchestras around the world, something the Soviet authorities had prevented him from receiving.

Slava checks his mail